Gonna make you sweat

Torn muscles, personal bests, and strategic toilet trips: inside the breathless world of endurance theatre

By Natasha Tripney

By the end of Miet Warlop’s One Song, the performers are absolutely soaked in sweat. They are saturated, their cheeks flushed, their hair damp. The perspiration is dripping off them. They look like they have just finished a particularly intense session at the gym, which in a way they have.

One Song consists of a single piece of music, which is played over and over again by the cast, who play instruments while at the same time performing feats of athleticism. The double-bassist is forced to do sit-up after sit-up to reach his instrument, the keyboardist bounces up and down on a springboard, and the vocalist runs on a treadmill. A pack of supporters – fans in matching scarves – stand on an upstage bleacher and cheer them on as the music speeds up, the tempo gets faster. It’s an exhilarating thing to witness and a gruelling thing to perform, with the performers required to simultaneously be athletes and musicians. We can hear their breathing as it becomes more ragged, watch as their gym kit darkens with perspiration.

As wonderful as it is watching highly-skilled bodies doing extraordinary things – an acrobat, say, or ballet dancer – there’s a particularly visceral thrill that comes from watching a performer pushing themselves to their physical limits. While every single performance is, in its own way, an act of endurance and a feat of stamina, some forms just feel more intense to witness, like you’re watching someone really go through something. As someone who is not particularly athletic, and finds most sports at best bemusing, I take a kind of weird vicarious delight in watching performers push themselves in this way.

Sometimes these physical gestures drive the show, like Sophie Steer bouncing on a trampoline for an hour in Antler’s moving miniature Lands; sometimes they are moments within a bigger thing, like an actor from Belarus Free Theatre sprinting in an endless circle during the entirety of the interval of Dogs of Europe. Both take their toll on the performer in different ways. (I remember Steer telling me that hiccups were an issue when performing Lands).

As in One Song, treadmills feature prominently in Australian collective Pony Cam’s Burnout Paradise, one of the big hits of this year’s Edinburgh fringe, which recently finished a run at St Ann’s Warehouse in New York. During the show, the four performers – Claire Bird, William Strom, Dominic Weintraub, and Hugo Williams – must complete a series of small and not-so-small tasks: cooking a meal, performing a dance routine, filling in and submitting a funding application (you can see why this was popular at the fringe), all while running at full pelt on the treadmill.

A device which could have felt gimmicky or obvious – the treadmill as a metaphor for the grind of life is not exactly an original idea – is made extra-compelling by the difficulty of what they’re attempting, be it preparing pasta, painting their fingernails or putting on a pair of pants, and by the inclusion of competitive element. Throughout the show, they’re both competing against each other’s times as well as their own personal best. To top it all, if they fail to complete their allotted tasks, they promise to refund everyone’s tickets (and have done so on many occasions).

“The competition drives the stakes of the work. We take that very seriously,” explains Pony Cam’s Dominic Weintraub. The idea for the show came to the company during a period of exhaustion. “We had gone two years without a holiday and were having these painful conversations about all of the things we were sacrificing to be in the space and how it was impacting our ability to collaborate with one another.”

The format of Burnout Paradise means the audience gets really invested in whether or not they complete the tasks, something that’s amplified by the fact we’re asked to help them, coming on stage and passing them items, or engaging in other activities, from wrapping presents to helping them write their risk assessment (essential in a show where the risk of injury is probably higher than average – Weintraub has fallen off the treadmill a couple of times and torn a muscle).

For Pony Cam, part of the joy of the show is that it’s a shared experience in which “we come together as a team, being friends and caring for one another.” There’s also the connection you get with an audience when you make work like this, a collective sense of release. “There's always this beautiful roar that happens at the end if we get the grant application done. It's like being at a sports stadium or scoring a goal in the final second.”

There’s also a balancing act to be struck in a performance that requires so much of them physically, but that also needs them to be able to talk to the audience throughout the show. It’s a real challenge, he says. “How do you communicate with an audience in a way that's sensitive and inviting, whilst also running as hard as you can whilst eating a banana?” You don’t want to pretend you’re not exhausted, because you are, he says, but you also need to “quell that just enough to be able to engage with people.”

Like the members of Pony Cam who all have sporting backgrounds, British performance-maker Jennifer Jackson was really into sport as a kid – her show WRESTLELADSWRESTLE is in part inspired by her experiences as a teenage judo champion – and she has a fascination with feats of endurance. She became interested in fell running and the fact that the people breaking the records in that field were often women in their 40s and 50s. “This really challenged what I thought was possible in terms of athleticism and sportsmanship.”

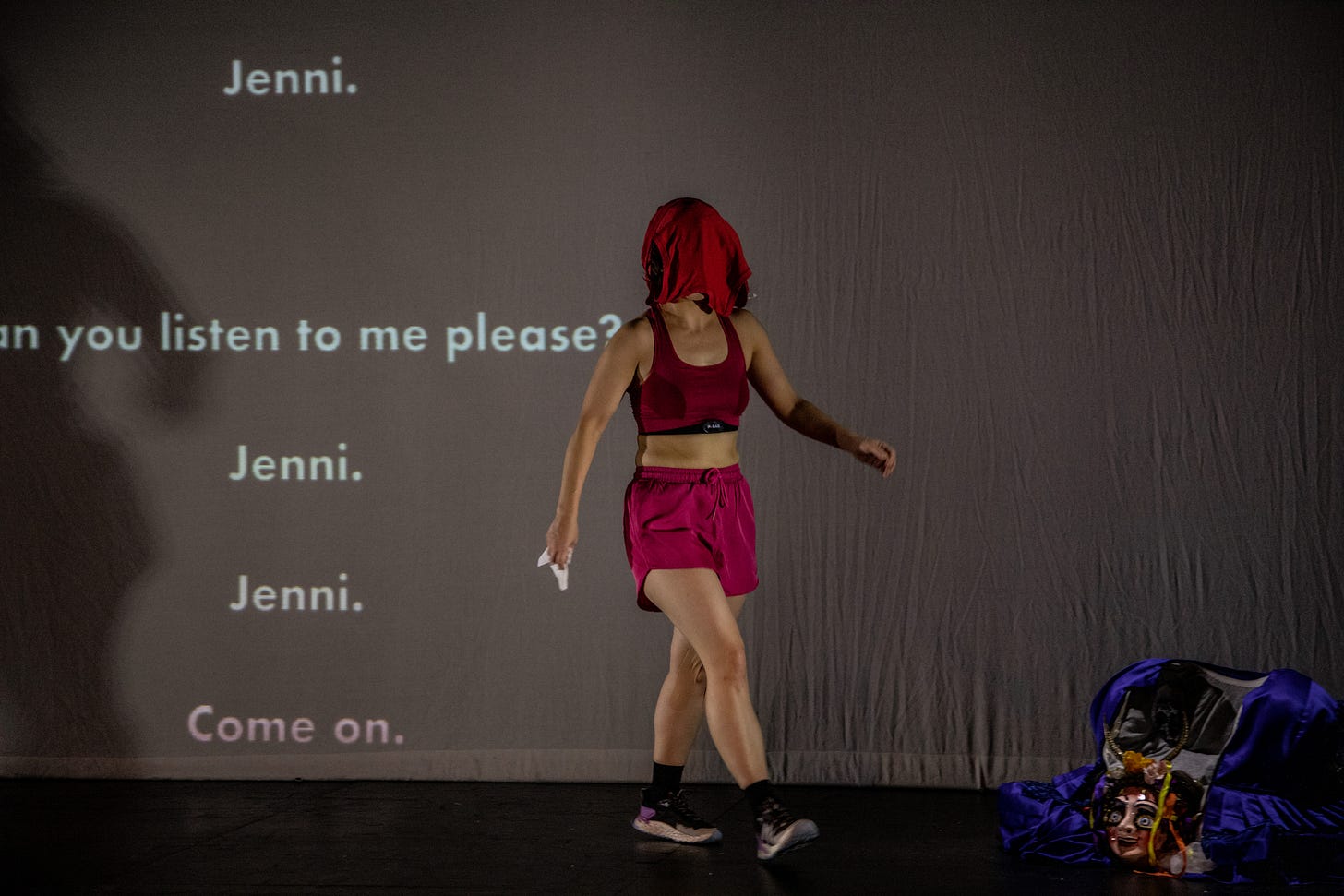

In her aptly titled show Endurance, having attached herself to a heart monitor, Jackson proceeds to run backwards and forwards in an arc across the stage, as the audience listen to the amplified sound of her breathing and the slap of her shoes on the floor, as well as the beep of the monitor.“I wanted to make a piece about running as a metaphor for getting up every day and going out in the world,” she says. At the same time, Jackson wanted the piece to acknowledge the oppression her Bolivian mother faced as a woman of colour. She was interested in the spectacle of “a woman's body being tested, eroded through a task like running,” the idea of what a body carries within it, in terms of genetic material and memory – the way her body is a vessel for her history and “all of the things that have come before me.”

Jackson initially considered using a treadmill in the show but decided against it. “It felt like I needed to be traveling as well,” she says. “The act of repetition, of putting one foot in front of the other became really important.”

The Mladinsko Theatre in Ljubljana has a reputation for making work that is often intensely physical: Slovenia has an ensemble system and the actors at the Mladinsko Theatre always impress me with their physical commitment. (It was here that I once saw an actor, naked but for a pair of roller-skates, scale the outside of a shipping container; here that I saw another naked actor slather himself in cream cake before skidding perilously around a theatre auditorium covered in plastic sheeting).

In Crises, a devised piece by the director Žiga Divjak, the actors enter the stage naked and proceed to dress themselves before spending the next 45 minutes running on the spot, picking up various items from the floor, backpacks, briefcases, shopping bags, children’s toys, coffee cups, and Amazon packages – like a game of human Buckaroo. With a show like this, says actor Vito Weis, “it’s so demanding that, from the moment you wake up, it dictates your whole day.” Like Jackson, he approaches the show as he would a sporting event. On the days when he’s performing, he needs to take a lot of things into consideration. “When is a good time for me to eat my last meal before the show? What should I eat? Did I get enough sleep? Should I take a nap in the afternoon? Should I go to the toilet?”

Weis’ work is often highly physical. In his solo show Bad Company, he ends up heaping folding chairs on top of his body, hanging them from his limbs and his neck until he is staggering under the weight of them all. In Slovenia Counts, another Mladinsko production co-directed by Sebastian Nübling and DJ Jackie Poloni, an insistent, pulsing beat keeps Weis and the rest of the cast in constant motion as they chant the word ‘Slovenia’ over and over again with varying levels of pride and aggression. It’s a challenging performance, intense, playful, full-on. By the end, Weis’ dark hair is glued to his forehead and the sweat patches on his T-shirt have joined together into one super-continent, to the extent that when he peels it off and wrings it out, perspiration pools at his feet. “If you want something that looks real, or that the audience feels is real, you have to be relentless toward yourself and the material,” he says of his approach to this kind of performance.

As demanding as these performances are, Weis points out that not moving at all can be just as challenging – as he discovered when starring in Divjak’s production of Duncan Macmillan’s two-hander Lungs. The director has him sitting stock still opposite the other actor for the whole show. “We’re sitting very still, and after one and a half hours of that everything starts to hurt, all of your muscles. It’s maybe not something you would judge as demanding at first sight, but it’s still very hard.” It was as gruelling, in its own way, as another production of Lungs: at the Schaubühne in Berlin in 2013, Katie Mitchell had two performers cycling throughout the whole show on stationary bikes, generating the play's electric power.

Weis is far from the only Slovenian actor I’ve seen who seems willing and able to push themselves to this extent (it’s probably why I find Slovenian theatre so exciting). I suspect this is at least in part a result of differences in their training compared to that received by many performers in the UK. Jackson agrees: “In terms of acting practice, no one is really trained to do this sort of work outside of dance.” Perhaps as a result, she would have felt uncomfortable asking someone else to perform Endurance. “I feel like I can put my body through something, because it’s my piece.” Making the show she was drawing as much on her sports training as a teenager as on her acting training, she says. “I was bringing a sports mentality to a theatre context.”

While Jackson gets a big adrenaline rush from doing the show, she also recognises the toll it takes and avoids taking on other work or drinking when she’s doing the show. When she first started performing the piece, she naively thought that while she was running around eight and half kilometres every night, as she wasn’t running very fast, she didn’t need to strap her feet properly. “Obviously your feet sweat inside the shoe, so I got these terrible blisters.” This made it very painful to perform. “You’re literally on damage limitation. It changes your gait. The pain makes you behave differently.”

Does the fact that pain is sometimes a consequence of this form of performance make it irresponsible? It’s a question Jackson finds interesting. “I’m asking the audience to witness me doing this to my body and putting myself through this,” she says. “At what point do they think that I'm being irresponsible with my body?” And how much does that matter given that this is a show she has created for herself to perform? “There’s a line around marginalized genders when we put our bodies into a performance space, or any kind of public sphere, that felt like it was exciting and a bit dangerous to explore.”

As well as the stamina required to perform shows like this every night, there’s also the stamina required to sustain a performance like this over a long period. Recovery needs to be taken into account. When I speak to Weintraub, he’s just coming off the back of a long run of Burnout Paradise in New York and still finding that his body starts “to get really fidgety and anxious at around 5pm, kind of stressed in preparation for a show that's not coming, but I’m still kind of ready each day to do it, physically, mentally.”

The space between the representational and the real has always fascinated me and work like this sits right in the spicy centre of that space. In the UK, so often when watching actors sweating through their costumes, their foreheads gleaming under the stage lights, it can feel like theatre is engaged in a kind of denial of the flesh, a rejection of the messy reality of inhabiting a body. The strain and effort are, if not concealed, then certainly downplayed.

This form of theatre is the antithesis of that. It is, in many ways, theatre at its most exposing. “I’ve only just started to understand that,” says Weintraub. “I’d always thought of this show as being pretty irreverent and playful and silly, which it kind of is – but there's something undeniably earnest and vulnerable about actually putting your body through something like that.”

One Song is at La Maison de la Culture de Tournai, Belgium, 8 Jan. Endurance is at the Playhouse, Sheffield Theatres, 31 Jan/1 Feb. WRESTLELADSWRESTLE is at the Playhouse, Sheffield Theatres, 12-15 Feb; Battersea Arts Centre, London, 4-8 Mar, and Cambridge Junction, 19-20 Mar.

For more brilliant writing about theatre from Natasha Tripney, subscribe to Cafe Europa

Well damn again! This puts me right in the theatre. It got my heart racing.