How revisiting The Years left me doubting my memory

Isobel Lewis gave The Almeida production five stars, and told everyone to buy tickets. But rewatching it has her questioning our 'recommendation culture'

By Isobel Lewis

When I purchased two tickets to a Wednesday matinee of The Years, I had no idea I was unpacking a can of critical worms that would leave me questioning my own memory. In truth, I had no intention of writing about the play, based on the book of the same name by Annie Ernaux, at all. What I think about this show is pretty clear; the pull quote used on the poster for the Harold Pinter Theatre transfer – “It moved me in ways theatre often tries to but rarely achieves” – is mine, as are the glowing five stars I, and many of my fellow critics, rewarded the production when it first ran at the Almeida in August.

No, my reason for returning to The Years was simple: I’d wanted to take my mum as an early birthday present, thus allowing her to share in the experience I’d had that summer evening watching the show. Being an arts journalist, I also live on an arts journalist’s budget. I either review from the best seats in the house (extremely luckily, I obviously have to caveat), or watch theatre for pleasure out of my own pocket from the cheap seats. The only remaining seats for this mid-week, mid-afternoon show were up in the balcony. The lightly restricted view was no bother; I’ve had some of my best theatrical experiences up there. Cricked necks can be worth it when they’re spent watching theatre as memorable as Marianne Elliott’s Company, which I saw from a £15 extreme restricted view side balcony spot and stays with me until this day.

My mum (I’m sure she’d want me to clarify) is a lot younger than Ernaux. She’s never read any of her work, either. Yet the first time I watched The Years, an adaptation of the 2008 hybrid-memoir considered by many to be the Nobel Laureate’s seminal work, I thought about her constantly. Told in the first-person plural, The Years is a story of mid-late 20th century Europe and one seemingly ordinary woman within it, where wars and the rise of consumerism are woven between health problems and divorce.

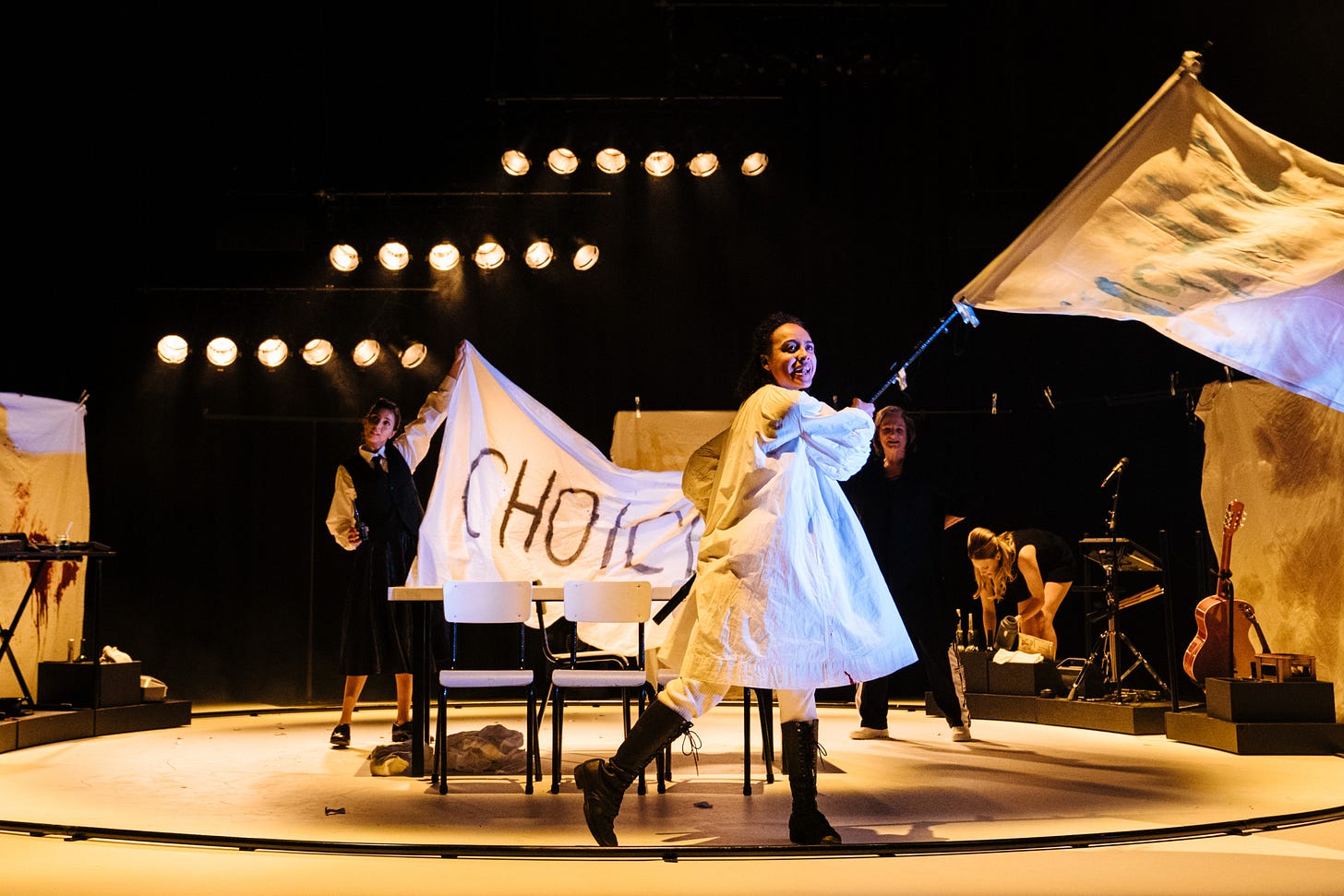

On paper, French writer Ernaux’s book is… not unstageable, but certainly a challenge to do so. Here, five actors (Deborah Findlay, Gina McKee, Romola Garai, Anjli Mohindra, Harmony Rose-Bremner) collectively embody “Annie”, as she is known, the cast remaining on stage for the entirety of the nearly two-hour, one-act run. I can’t even imagine how emotional they must feel at the end of each performance; watching director Eline Arbo’s production at the Almeida alone, I left the theatre a weeping mess.

Within a whirlpool of laughter and pained cries, singing and synths, these five actors collectively created a seemingly normal life from birth to old age. Love, loss and sexual experiences joyous, painful and muddy were all major emotional beats in Annie’s life that played out before our eyes in snippets and photographic tableaus. In doing so, they let us into her very soul: the soul of all womanhood.

At some point – I think when McKee became our penultimate Annie – tears formed in my eyes that fell consistently through Findlay’s final turn. I remember waiting at the bus stop afterwards and feeling this huge, overwhelming urge to call my mum for the second time that day. Inside was a desire to know the beats of her life as I now did Annie’s – even the seemingly mundane ones.

Writing that down, I can accept that this is a hell of a lot of baggage to bring to the theatre, and that getting to see The Years with my mum was important to me in ways it understandably wasn’t for her. She was looking forward to seeing a show I’d raved about; I, conversely, wanted to open up my memory and beckon her in. Given Ernaux’s own fixation on memory, it’s all sounding a bit meta. Yet I hadn’t considered any of this until I was watching for a second time and realising that my expectations weren’t being met.

It’s hard to put my finger on precisely what changed for me in my second viewing of The Years. I still enjoyed it, but in the hours and days after was left with this strange feeling that something was off, I guess. I wouldn’t chalk it down to third preview jitters; in fact, I felt that the consistently strong cast were somehow performing more cohesively than ever. Bar the performance being interrupted when an audience member felt faint (which also happened at a friends’ showing the next day, and is virtually part of the production at this point), I think this was the show operating exactly as intended. And it has duly won another slew of four and five star reviews.

As far as I could tell, the only technical difference was the decision not to recreate the Almeida’s iconic curved back wall, and instead place Juul Dekker’s set against a black box. A strange decision: obviously you can’t blame the Pinter for not being the Almeida, but plenty of Almeida transfers have featured a recreation of the wall. One can currently be seen just down the road in the final outing of Rebecca Frecknall’s A Streetcar Named Desire – in fact, I have it on good authority that there are multiple duplicates in storage that are pulled out and used over and over again. The black box, comparatively, felt hollow in ways that first production hadn’t.

That loss of intimacy is what underpins everything that felt a bit off to me with this second run. The Pinter, I believe, is too big a space for a show that celebrates smallness like The Years. The magic of Arbo’s production comes from looking back at the last two hours and realising little has happened yet you are irrevocably changed. In that cavernous space, it felt limper; a catch 22, I realise, after hoping a transfer would allow more people to get to experience The Years.

Then: that much-feted abortion scene. On first viewing of The Years, I felt the headlines about men nearly fainting to be an overreaction. The scene, performed by Garai, was certainly gnarly, but the hardest part to handle were her words and groans, not the blood. In The Years’ new home, Garai has to play to the back of the auditorium. From my lofty view, I could see the working of the scene more, yet strangely this shattering of the illusion made it a lot harder to bear. It was as though if I could believe the scene was real, then the pain the audience was put through was worth it; as soon as it felt false, an uncanniness emerged and Garai’s wailing felt less earned.

If this took me out of the show, having the scene interrupted – while no fault of the production – only heightened this. During the 20-minute break while an audience member felt faint, my eyes kept returning to the woman in front of me who had switched off airplane mode and returned to the crossword on her phone. It felt totally at odds with what we’d just seen – what we were in the midst of seeing, really. Sat beside me, my mum asked if there had been any content warnings about this scene, and I was hit with a guilt that my own cavalier attitude had led to me downplaying this moment to her.

In the days that followed, I struggled to shake that feeling. Taking my mum to see The Years felt like a more expensive version of when you make a friend watch your favourite film with you: really, it’s their reactions you’re looking out for. And the thing is, she did enjoy the play, yet I couldn’t let go of the intense frustration that it wasn’t the show I’d wanted her to see. My mum was watching The Years because of me, but she’s not the only person – directly or indirectly – to have bought a ticket based on my recommendations. Two of my closest friends were watching the show the following day. Knowing their tastes, I suddenly panicked that they, and the people I’d recommended purchase tickets as Christmas presents, wouldn’t be wowed.

For the sake of argument, I’ve focused here on my issues with the production. To clarify, I loved the emotion of the script and performances as I had the first time around, with McKee and Findlay’s chapters still the stand-outs. Yet I hated that I’d, not 180’d, but turned back 90 degrees on this show I’d previously declared my best show of 2024. What kind of critic was I if I couldn’t stand on my convictions? Getting caught up in the show’s meta focus on memory, I briefly found myself questioning whether I’d overhyped the Almeida production to myself. But flicking back through my miniature review notebook, there’s clear passion in even my scribbled jottings. I felt what I felt in that moment, and shouldn’t forget that.

What I’ve been stewing over since is the difference between a review, which claims to be subjective, and a recommendation, which (I’d argue foolishly) is taken to be more objective. A recommendation, even a vague platitude on social media, is a way of saying that you think another person will likely enjoy a show; reviews, as we are forced to reiterate, are just one person’s opinion. It’s up to the reader to decide whether the critic’s individual opinion makes them want to purchase a ticket or not, because every critic comes to each performance with their own life experience.

In my case, I have read more of Ernaux’s back catalogue since watching The Years the first time – perhaps, with an enhanced knowledge of her work, I’m aware of the depth that naturally will be missed when The Years is shrunk down into two hours. That’s my own baggage.

But as criticism becomes more streamlined and less funded, the pressure to swap out thoughtful reviewing for SEO-driven articles looking to capitalise on the search terms “best London theatre” is stronger than ever. And look, I love to recommend. The thrill when someone tells me they went to a restaurant after hearing me talk about it? There’s nothing better than that validation of your taste. But writing about theatre is my job. At times, I, too, struggle to remember that there’s no such thing as “objectively good” theatre, but deep down I do believe that it’s the sanctity of subjectivity that makes criticism an art form of its own.

And I get it! We all know that feeling of frustration when something you spent your money on with high hopes doesn’t live up to them. Yet funnily enough, it’s only while writing this that I’m suddenly reminding myself that my second viewing of The Years also elicited a subjective opinion with equal validity, and that I’m projecting a lot on my mum and fellow audience member’s opinions of the show. Who am I to say that her experience of the show was lesser just because I believe she saw what I deem to be a less singular version? And isn’t it a little self-important – arguably even patronising – to suggest that anyone who saw The Years on my recommendation and didn’t leave feeling profoundly changed would hold me directly accountable?

So the next time I walk past the Pinter and see my own words quoted back to me or glimpse them on the tube, I will resist the urge to feel that shame and guilt. Reducing an experience to a pull quote recommendation, while part of the reviewing game, is always going to be a reductive exercise. But my second viewing garnering a different reaction doesn’t mean what I saw that first time – and my memory – was wrong. I stand by the five stars I gave The Years at the Almeida, because they were the easiest I’d given in years. Equally, I can back the high three or caveated four I would probably give the West End transfer. Both experiences hold equal weight, and one memory does not invalidate the other – an Ernaux-ism if ever I’ve written one.

The Years is at the Harold Pinter Theatre to 19 April

For more from Isobel Lewis, subscribe to her Substack Platescraper

I saw it at the Almeida too and loved it, although perhaps not as much as many critics and acquaintances. Whilst it was fantastic to see five women on the stage, I felt less engaged with the younger depictions of Annie and would have preferred those sections to be shorter. The intensity picked up when we got to Romola Garai though and Gina McKee was heart-stoppingly good.

The response to it was so overwhelming that it was an obvious candidate for a transfer and I did wonder if it would work as well in a larger space - so often a game-changer for a production. I also knew that I wouldn’t go and see it again. Sometimes big impact plays are best experienced only once.

Conversely I just saw Asa Butterfield in Second Best in the large hangar-like space at Riverside Studios and thought it would feel truer and less overly slick in a smaller room.