To boycott, or not to boycott?

What role should theatre-makers take in the sponsorship debate? A group response, and an invitation to discuss

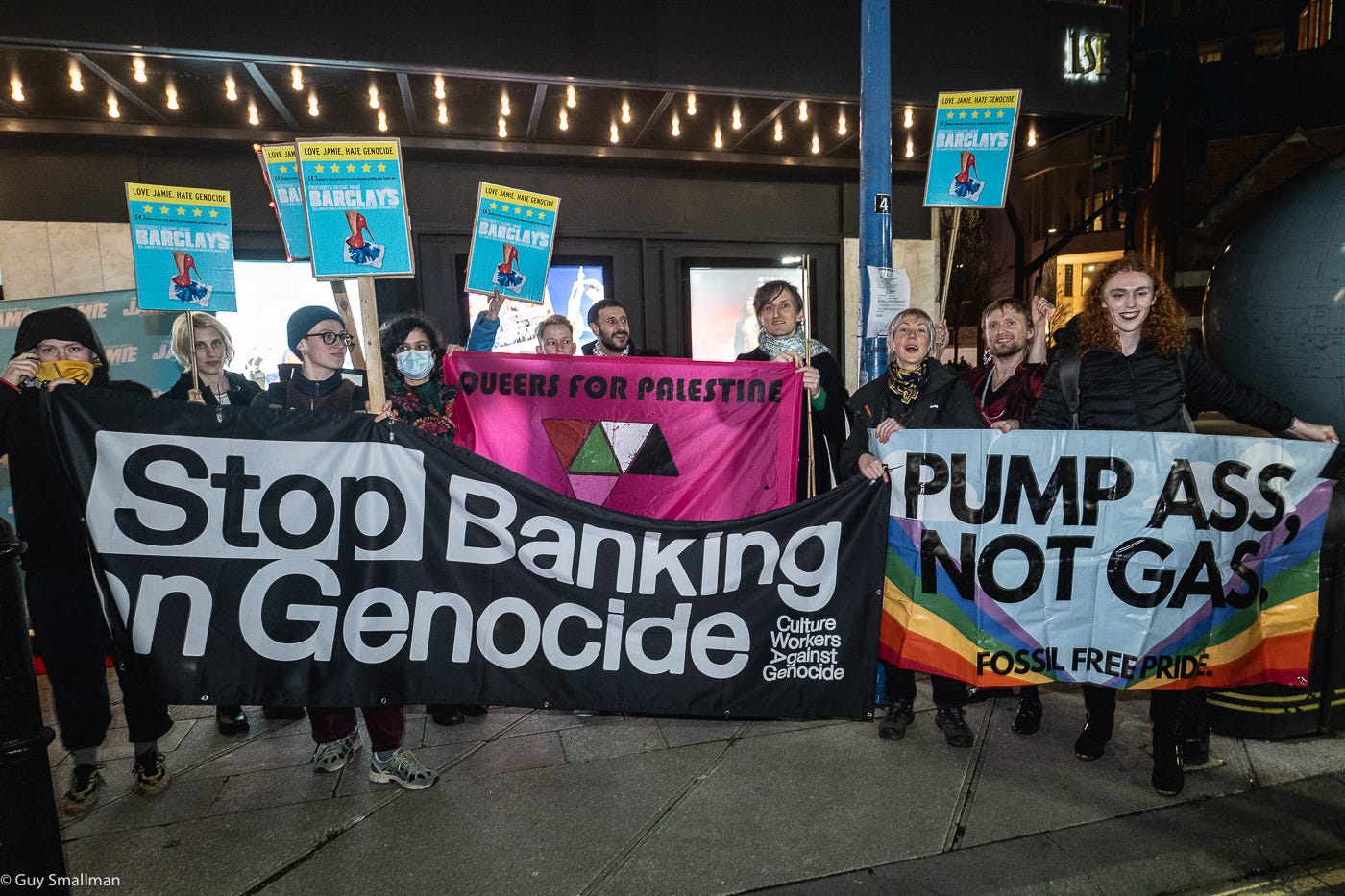

This isn’t an essay so much as an invitation, shared in the wake of Caryl Churchill breaking ties with Donmar Warehouse in protest at its ongoing relationship with Barclays. Churchill made a clear statement of boycott, a demand for divestment from a business trading with arms companies that supply Israel. It’s a demand that activist groups such as Culture Workers Against Genocide are calling for more widely, yet few people are replicating. I’m among the complicit: when offered a day of work this year with a venue also funded by Barclays, I said yes: a yes conditioned by articulating discomfort at the sponsorship, but still a yes.

Anything that makes me uncomfortable inclines me towards discussion, taking seriously the Audre Lorde tenets both famous – “Your silence will not protect you” – and lesser-known: “It is not difference which immobilises us, but silence.” In a vexed climate of polarised thinking, however, discussions based in difference of experience can be difficult to conduct. Hence this invitation: to collective thinking, even conversation if that feels possible to you.

To open that dialogue up, I drew up a few basic questions and shared them with 16 people – and now also with you.

What is useful or necessary about boycott and divestment as a demand in theatre?

What can boycott and divestment achieve that, for instance, staging work by Palestinian artists can’t?

What are the risks for artists in divesting from and boycotting venues?

What about the risks for organisations in relation to funding opportunities? Especially small organisations?

What role might critics play? Should we refuse to write about work at venues refusing boycott or divestment?

If boycott doesn’t feel like an option, what might we do instead?

Of the 16 people I approached, the five who agreed to participate are an interesting cross-section of industry figures. They include an established director (Kirsty Housley), a young playwright (who will remain anonymous, at their request), an organiser with Culture Workers Against Genocide (Rida Hamidou), an artist-activist (Jay Jordan), and an elected representative from the actors’ union Equity (also remaining anonymous). Differences in age and role as theatre-workers make for nuanced differences in how they approached the questions; at the same time, we focused on some questions more than others, and if, for instance, a critic had responded, it would have shifted the direction of this essay.

And there is one commonality: none of these people agrees that boycott and divestment demands have “the potential for ‘killing off’ arts and culture in the UK”, to quote Alistair Spalding and Britannia Morton, co-CEOs of Sadler’s Wells, and a bunch of unnamed arts leaders from venues including Donmar, National Theatre and Edinburgh International Festival. These are old arguments, used decade after decade, by arts leaders who would rather destroy life than change it.

Those are my words, my judgment – but from here on what you’ll read is a collective voice, spoken by an “I” that moves between us, sometimes within a single sentence. In editing this together I’ve been inspired by the excellent, multi-authored book Empire’s Endgame, and use this approach because I want the focus to be on ideas and modelling coalition, not on individual personalities. There are more differences in approach and argument than I’ve been able to represent here, thoughts shared with me privately that refused to be made public. But that doesn’t mean we all think the same or are taking the same approach. And so, along with the questions, this comes to you with the invitation: to recognise the complexity and nuance in how this group discusses a too easily polarised debate. - Maddy Costa

Strategies for resistance

In the 17 days between sending the first emails and beginning to collate this, the UK government began threatening to categorise activist group Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation. It was also revealed that, as a lawyer in 2003, Keir Starmer defended acts of military sabotage as “legally justified because it might stop a war crime” – that is, the US-led, UK-supported attack on Iraq. What’s changed between then and now is how explicitly we inhabit a fascist-leaning environment. In that place, all acts of humanist protest feel fraught.

Which makes BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) all the more useful as a strategy. It’s an easy, peaceful way to apply pressure, and has always been a really important part of pushing for change, whether it’s applied to brands and organisations, theatres or nations. We know it works: cultural boycotts played a crucial role in isolating apartheid South Africa, weakening its legitimacy and inspiring public and political pressure.

Boycott is important because of what Platform, a campaigning and research group, calls the “social license to operate”. Corporations spread the idea that they’re there to help art: they’re there to fund art, they’re there to support art. In fact – and the thing that a lot of people forget – it’s the other way around. The art is there to support these corporations in their process of green-washing, art-washing, genocide-washing. Art is a very, very, very good tool for this. Brands who, behind the scenes, send weapons and tech components to a government that’s been breaking international law for decades, appear to be doing good by supporting the arts, while arts organisations frame these companies as “ethical”. Increasingly, in the past 40, 50 years, we’ve seen art institutions become annexes of the PR work of these corporations.

Censorship, implicit and direct

When a venue chooses to keep working with complicit funders, it shifts the ethical burden on to artists and staff, forcing those who take a stand to risk losing income, work, visibility, and future opportunities. These are often the same people whose identities are used to market the apparent success of a theatre’s disability, equality and inclusion strategies, but who also lack real security, influence, or decision-making power within those institutions. Being forced to choose between personal conscience and professional survival is a symptom of institutional failure. It is a failure of leadership when directors of buildings knowingly put artists and culture workers in that position.

We’re in very dangerous waters at the moment, with arts organisations banding together to discredit and shut down artists who don’t want their work funded with blood money, or audiences who don’t want their tickets subsidised by fossil fuel and weapons investment. Perhaps I’m hopelessly idealistic, but I want my arts organisations to question, to hold power to account, to want to make the world a better place. And we can’t do that when these sponsors are seen as paying us. I know from my experience of working within organisations that take these deals that having these sponsors directly impacts what artists are allowed to say and do: both in their work and in their personal lives. And that is dangerous. It’s censorship.

Organisations are doubling down and writing into the contracts of companies and artists that they cannot speak critically – even as individuals – about the organisation’s sponsors without breaching their contract. This puts certain artists, particularly young artists, more at risk than others. I don’t have the sway of Caryl Churchill; I don’t feel my voice or actions have any sway at all. And how many writers will have this sway in the future, when we’re operating in a climate where less and less new work is being commissioned and made? It feels huge to cut ties with venues when the opportunities for work are so scarce. I’ve done this with a couple of jobs and the result wasn’t pressure for internal change, but simply me not having those jobs any more, and the internal problems getting worse. It obviously means more when it costs us, but I worry whether anyone will really listen or act. As a result, I feel very, very disempowered.

I’m totally dependent on my income to provide for my family and, if I’m being completely honest, whether I’m able to choose not to work in organisations with funding that’s connected to weapons or fossil fuels is very dependent on what else I have happening that year, and how compromised I and other company members might feel.

In reality, my stance probably makes it less likely that some of those organisations would commission my work in the first place. The most potent form of censorship is the implicit. It’s what you can and cannot be seen to say in advance of being engaged on a production. That’s true for trans artists, it's true for pro-Palestinian voices, it’s true for people on the left in general. Campaign groups on every issue – even employment rights issues – are quieter now than they were 10 or 15 years ago because the industry is so precarious.

It’s interesting that the key voices in the pushback against BDS and unethical sponsorship are some of our largest organisations. There are many small organisations who are making tough choices about what money to accept and reject. Nobody is asking for perfection, and it’s not always clear where a line can and should be drawn. But no arts organisation would accept money directly from Lockheed Martin, or BAE systems. So why should money that’s been grown from investing in those industries be any different?

I am getting a real sense of venues having battened down the hatches by making their internal processes more opaque. They can then always say, yes, we’re working on things on the inside, without ever committing to anything concrete. There’s a pressure to not be a “bad sport” since venues are “doing their best” in the “challenging funding landscape for the arts”. Accountability has been decimated.

Public-private partnerships and the concept of risk

We’re more than three decades into the Private Finance Initiative: a governmental policy launched by John Major as Conservative prime minister, mutated by the enthusiastic embrace of the New Labour government, and slanted towards even greater private sponsorship by successive Tory governments who used austerity as an excuse to slash public funding. We need to shift the wider culture so that the whole ecology of funding is seen as problematic. The state should fund public institutions and nobody else. As a trade unionist and as a socialist, I don’t care how “good” the private money is, I don’t want it in the arts. I want art to be funded at arm’s length, and sometimes directly, by the state.

Organisations like BP receive enormous tax subsidies from government – meaning less public money is available for art, education, the NHS. These tax breaks cost us millions as a nation: if they were taxed fairly, would we need private finance at all? It depresses me that NOT ONE of the arts leaders arguing in favour of this sponsorship is talking about how fair taxation of the biggest businesses could increase public funding and leave us free of their influence.

Morton has argued on Radio 4 that without money from Barclays, Sadler’s Wells wouldn’t be able to take the risks they do, and how it’s really artists and audiences who would lose out. In the short term this might be true, but this is also a lazy argument, and we owe it to ourselves, our audiences and the world to do better.

When you actually look at the sponsorship figures – which are very hard to get hold of – the amounts are tiny, absolutely tiny. The same argument was used against Liberate Tate (the campaign that ended BP’s sponsorship of Tate in 2017, after 26 years): Tate insisted that we were going to stop people having access to art. Which we now know is bullshit, because the amount of money that they were getting has nothing to do with ticket prices. The fact that so much current sponsorship is presented as enabling access for low-income or young people is very clever: essentially, it’s weaponising art-washing against you.

The fact that the biggest financial growth areas (and therefore the industries with the most money) are the most violent and destructive ones, should be telling us something urgent about how fucked this economic model we exist within is. There are other corporate sponsors who aren’t financially underwriting a genocide. I’d like our arts leaders to be pushing back against this risk argument, not climbing into bed with it. When we let our work be part of the legitimisation of these industries, we are complicit in their actions. The bigger risk – to our shared humanity at least – is silence.

It’s slow, but we will win. Israel’s leaders are currently on trial for genocide at the International Court of Justice: as a result, the global duty of non-assistance has been triggered. This is a binding legal obligation that prohibits states and organisations around the world from supporting an ongoing genocide. Senior figures at companies like Barclays, people like Nigel Higgins, who also chairs Sadler’s Wells’ board of trustees, may potentially face legal risk related to financing arms suppliers to Israel. Theatres that continue to partner with companies like Barclays risk significant reputational damage through association. In the long run, that damage is likely to outweigh any short-term financial security corporate sponsorship provides.

Converts not heretics

In March 2021, Equity joined a TUC-organised march – not a Palestine Solidarity campaign, nothing that we’re not affiliated to – and it became a media horror show. It was a stress test of the union by a particular set of pressure groups to see whether the union would buckle or change. Over the course of this debacle, which involved articles on Newsnight and front pages of national newspapers, 50 people contacted the union – out of a membership of 50,000 – and half of that 50 threatened to leave. All of those people were offered a personal conversation with Equity staff, and the union position was explained to them: Equity has a dignity at work policy supports people who boycott institutions, but doesn’t have a boycott policy itself; Equity has long had a position of no investments in armaments or tobacco, and we’re no longer investing in fossil fuels. As a result of those conversations, half of those people decided to remain as members.

Is it morally or ethically satisfactory that we don’t take a BDS position? Probably not. But our voice is always going to be against a tidal wave of appalling fear that is placed in people, and to take people from fear to a better place, you’ve got to be a movement of converts, not heretics. That requires keeping our members engaged with the conversation through material, not performative actions: that is, through workers’ struggles. The union is not the sole source of action, not the be-all-and-end-all of struggle. You have to have campaign groups to do the stuff that we can’t, while we give voice to those demands in a different way.

Theatre – or life?

Ignoring the call of the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement – the largest coalition of Palestinian civil society groups – while staging Palestinian stories is cultural appropriation. It extracts narrative without honouring the political demands behind it. It soothes the conscience of the institution and its audience without meaningfully interrupting its complicit alliances. Theatres cannot claim to stand with Palestinians while ignoring their clearest, most consistent demand.

Just showing the world to people is not enough. Are we just going to do another play about Palestine, or just another play about climate catastrophe? Art and theatre can transform the world if it’s integrated into real political movements, but not if it’s this thing, separate, apart, on a stage, in a white cube, in a black box. These things are inventions of the white metropolis: the white-supremacist, colonial, patriarchal, capitalist modernity that sees art as a pinnacle of civilisation, more important than everything – even more important than genocide, in a way. We need to bring art and theatre back to everyday life; we need a radical transformation of all these structures.

These things are always slow, but I believe that the creativity of artists can transform things deeply, if they have the courage to let go of cultural capital. This isn’t the same as allowing yourself to be censored. It’s about refusing this binary of self and world. Yes, you’ve been trained to think that it’s all about you and your career, rather than you as part of a wider social-ecological system that you are responsible for and interrelated with. We need to work on ending all these dualisms, to continually push for a non-dualistic culture in which it just won't be possible to think it’s OK for a life-destroying corporation to fund art.