Why Richard II deserves to be more than a star vehicle

Jonathan Bailey may carry the show - but for Hailey Bachrach, celebrity casting risks stripping Shakespeare's history plays of their true tragedy

By Hailey Bachrach

The endurance of star-studded West End productions of Shakespeare suggests that William still stands tall as a yardstick against which any true actor is expected to occasionally measure themselves. Sigourney Weaver’s recent turn as Prospero is a high-profile example of what critics seem to agree was an actor outmatched by the demands of Shakespeare, but there have also been a spate of well-received Romeo and Juliets in both London and New York starring young, talented TV stars, and some Macbeths and Hamlets for the slightly older ones. Shakespeare is a frequent vehicle for film and TV stars looking to make their stage debut or, to reaffirm their live theatre cred after some time in Hollywood. And while you’ll see the occasional bold swing – Ralph Fiennes’ Mark Antony, for example, or Tom Hiddleston as Coriolanus or even currently as Benedick – Hamlet, Romeo, Juliet, Macbeth, and his Lady all fall neatly into a category of ‘standard’ Shakespeare star vehicles that play a crucial role in letting stars establish themselves as performers with traditional textual chops and the skill for live performance.

Jonathan Bailey has spent the past several years as a screen star on the rise, specifically as a heterosexual heartthrob in the smash hits Bridgerton and Wicked. A cheeky Bridgerton-themed Romeo might have been a good guess for how he’d herald his return to the stage – or, given his long experience with live performance (and maybe being a little old for Romeo), perhaps even Hamlet. But Bailey has chosen the title role in Richard II at the Bridge Theatre, under the direction of artistic director Nicholas Hytner.

Much has been written about the similarities between Hamlet and King Richard in their melancholy and introspection, their flair for the dramatic and their fourth-wall-prodding ability to self-consciously become the playwrights of their own lives. In my own extremely biased view, having recently written a new introduction to the play for the Oxford World Classics series, I think it’s a role of equal richness and challenge to Hamlet. And it has indeed not only been used as a star vehicle throughout its history, but in recent years, its relative obscurity has meant that it is almost never performed without a star, including David Tennant, Adjoa Andoh (also of Bridgerton fame), and Simon Russell Beale. The same, in fact, could be said of more or less all of Shakespeare’s English history plays, my favourite genre, but one that is seen to scare off audiences without a known name to tempt them to give it a try.

Hytner’s Bridge Theatre has made star-studded Shakespeare part of its standard repertoire since opening with Ben Whishaw (himself a former Richard II, in the BBC’s The Hollow Crown) and Michelle Fairley in Julius Caesar. Bailey’s debut there times perfectly with his ascent to a new level of fame as the dashing Fiyero in Wicked. But Bailey’s live performance roots – his comfort onstage and with Shakespearean text – are both obvious from the start of a production that relies heavily on his skill for shape and pace.

Much like Hamlet, Richard II is a play that can feel like a rich ensemble story, or just a one-man show. It is the tale of an indisputably bad king, Richard, whose overthrow by his cousin Bullingbrook forces king and country alike to face who they really are. Though Richard does not soliloquise as often as Hamlet, they are alike as men forced, by a brutal loss of certainty in the order of the world as they understood it, to find a way to re-make themselves. And both, by most measures, fail.

Bob Crowley’s designs are the now-classic history play political chic, modern suits and the trappings of the present day: a hospital bed, a desk and microphone for a tribunal, a referee’s whistle at a trial by combat. Even as Richard lounges snorting cocaine with Aumerle, there are attendants on hand with suit jackets and clipboards, perpetually emphasising that this is a political story about a man who lives his life in public. It makes the one scene set in an ordinary home – well, ordinary for extremely wealthy people, with a well-appointed kitchen table and the Duke and Duchess of York clad in pitch-perfect ‘rich folk in the country’ gilets and wellies – stand out starkly as an exception to the rule, a tiny glimpse into the types of dynamics the production is otherwise uninterested in.

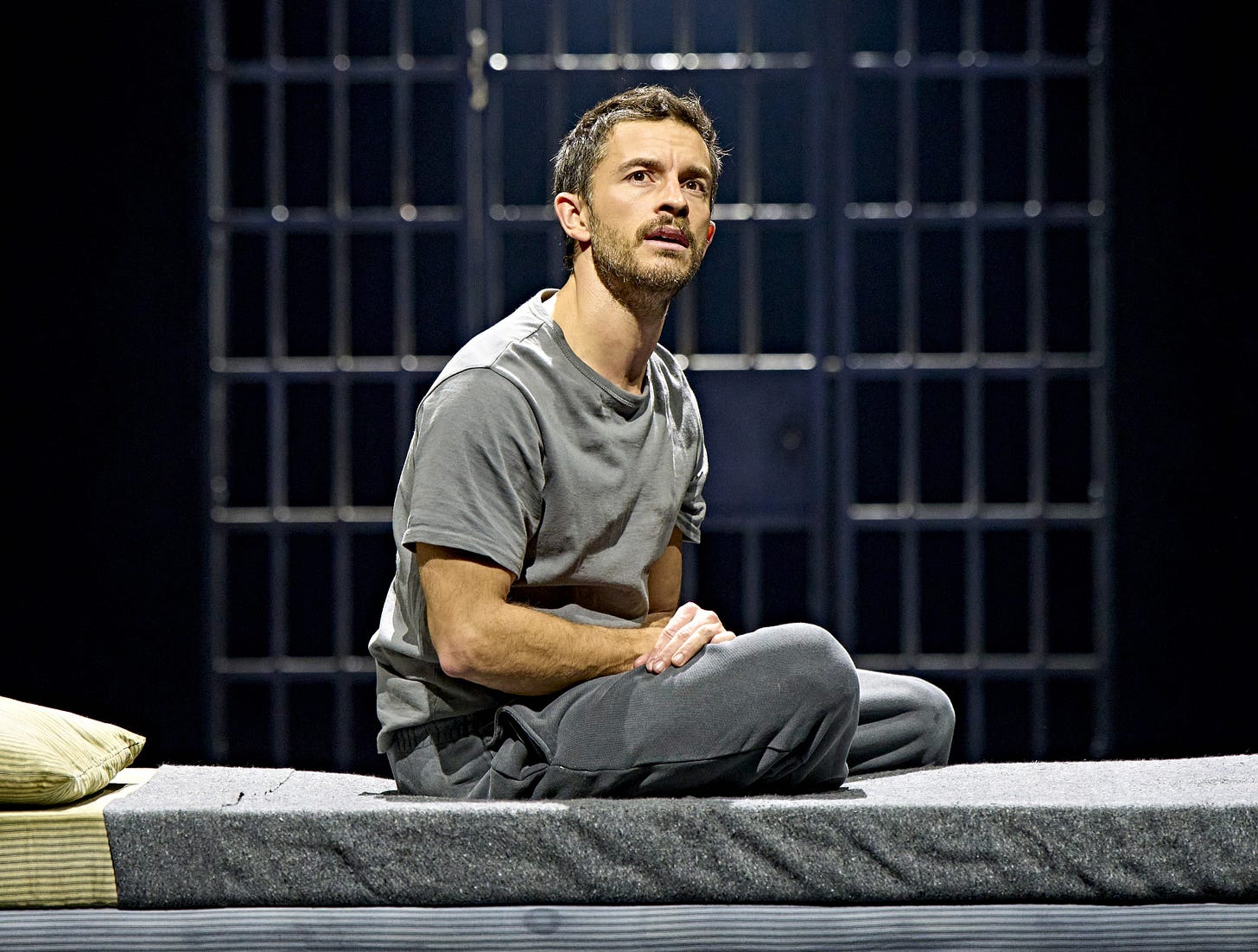

Bailey’s take on Richard fits this framing perfectly. While the play can sometimes be seen and performed as the gradual peeling away of Richard’s pomp and arrogant regality until only the man is left behind, Bailey instead suggests that there may be no true self here. Even as he rots alone in prison in his final scene, Richard cannot suppress the flashes of fussy arrogance that characterised his time as king – paired, now, with a touch of rueful self-awareness, but not enough to keep himself from slipping back into the habits of kingly posturing.

Charming and handsome, Bailey does not play into the bratty impotence that very often characterises the role. It’s an understandable take: the play begins with Richard’s utter failure to command two fractious subjects, leading to him setting up and then immediately interrupting a trial by combat in order to reassert control. Bailey sees the calculation here. His Richard keeps his cool, on the whole, seeming to already know what scene he will stage in order to reassert his power.

As Richard’s power slips, so does his control over his anger and sadness, but even there Bailey suggests a man who has never learned sincerity. Richard’s overall lack of soliloquy has rarely felt more deliberate: Bailey’s Richard cannot express himself except as a performance for others. The production therefore feels less like the tragedy of a fall, and more a study in a man warped by an excess of praise and power. A different kind of tragedy, and arguably one more fitting for our times.

Hytner’s unsentimental cut to the text – which I can’t help but respect for its ruthlessness in excising even famous (I realise this is a relative term with a play like this) scenes and characters such as the gardeners who discuss Richard’s deposition or his aunt the Duchess of Gloucester – renders most of the other characters too thinly drawn to command much attention. The exceptions are Michael Simkins and Vinnie Heaven as father and son Duke of York and Aumerle, and Royce Pierreson as Bullingbrook.

These three characters are the vestigial centre-points of the text’s rich web of interpersonal drama, the York family in particular representing Richard’s embeddedness in a history and lineage that is as much about brothers, uncles, and sons as succession. Simkins’ charmingly put-upon line delivery is a welcome note of contrast to both the self-serious politicians and Richard’s drama, while Heaven captures Aumerle’s determined passion as a true believer in Richard, someone whose intelligence and loyalty are overshadowed by their flippant manner.

Aumerle is often key to the play’s queer readings, which is partly achieved by casting nonbinary actor and writer Heaven in the role here, but aside from a brief, flirtatious nuzzling of cheeks whilst high on cocaine, Hytner eschews the now all-but-obligatory explicit romance between Richard and Aumerle (as seen in both David Tennant and Adjoa Andoh’s Richards), or any particular commentary on either character’s sexuality. This rejection goes as far as to cut the most famous ‘evidence’ for a queer interpretation of Richard, a line in which Bullingbrook accuses two of Richard’s favourites of having “with your sinful hours / Made a divorce betwixt [Richard’s] queen and him, / Broke the possession of a royal bed” (3.1.11-13).

It isn’t rare, in performance or scholarship, to miss the importance of the kinds of apparently inconsequential scenes that Hytner largely does away with. But the production feels rushed and thin without them. The women, the implications of sordid gay affairs, the gardeners and common soldiers, Richard’s extended family members and the families of his enemies and allies, are the soil for his individual tragedy to root and blossom into something that feels bigger than just one man. And the beauty of this play in particular, uniquely amongst all of Shakespeare’s plays, is that it elevates and glorifies all of these characters with the dignity of poetry: it is the only play written entirely in verse. I can think of no clearer sign from Shakespeare about how much every single voice in the story matters.

The beginnings of each act frame Richard and Bullingbrook as mirrors – two buckets in a well, as Richard describes them, one rising with the other’s fall, but otherwise identical. Pierreson brings compelling gravitas in contrast to Richard’s theatrics. His Bullingbrook understands the need to put on a show, but displays this canniness through pragmatically-delivered delegation, leaving the actual performances to others. But the slapdash pace of Hytner’s heavily-cut scenes leave him no time to establish himself as an actual equal to Richard within the narrative. This is Richard’s story: one man poised against the masses who oppose him.

I can’t help but miss how the text itself reflects Shakespeare’s own understanding – actually outlined in one of the scholarly essays in the programme, though not reflected in the performance – that Richard II, and indeed any dynastic drama, is a family tragedy. The perceived necessity to place a star at the heart of this and other history plays reinforces the centrality of the main, usually titular, character, and in doing so also perpetuates the idea that Proper History is the tale of singular individuals rather than communities.

It likewise reinforces Richard’s own sense of himself as someone too singular, too important, to simply have to face the consequences of his poor rule, or be swept up in the tides of events beyond his control. In this production, he is right: there is a world beyond him, but only barely. Though Bailey resists the temptation to plead for empathy for this self-centred tyrant, Hytner insists that his is still the only story worth hearing.

Richard II is at the Bridge Theatre, London to 10 May

Richard II is published by Oxford World’s Classics 13 May, or available as an ebook now